1. One topic that I could research is the role that Abraham Lincoln's personal beliefs played in the beginning of the Civil War. I am also interested in the federal policies that Lincoln enacted during the war.

Questions concerning this topic:

Was Abraham Lincoln a Christian?

Did he desire equal rights for black slaves, or just their emancipation?

Was the Emancipation Proclamation created as a political move, as a strategic military move, or was it created because it was the right thing to do?

2. I could also research why the Confederates felt that their cause of succession and slavery was the right and noble path during the Civil War. This would help me explain why the Confederate Army was so willing to fight and die for a cause that we now view as abhorrent.

Questions concerning this topic:

How could the Confederates view their cause as being noble?

If so, did this make them more dedicated soldiers?

Did the Confederates plan to have slavery instituted in their new nation forever?

3. A third topic that I could research is the role that African Americans played in the Union victory over the Confederacy.

Questions concerning this topic:

How many African Americans fought for the Union, and what were their roles in the army?

Did any slaves in the Confederacy do anything to damage the Confederate cause? If so what did they do?

Were their any slaves who fought for the Confederacy? Why or why not?

Friday, April 19, 2013

Friday, April 5, 2013

Interpretation of Primary Sources

|

| From www.smithsonianmag.com |

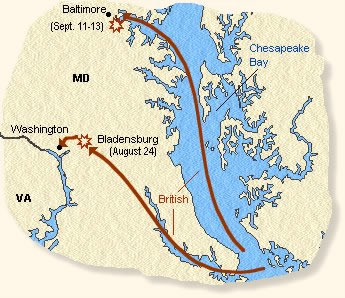

The mood that I have drawn from these sources is supported by Jon Latimer in 1812 War with America. In chapter 14, Latimer discusses the burning of Washington from a British perspective. The British mood of confidence is best exhibited by Cockburn (admiral and colonel of the Royal Marines) who proposed and led the attack on Washington. In a private letter Cockburn says, "I most firmly believe that within forty-eight Hours after the Arrival in the Patuxent...the City of Washington might be possessed without Difficulty or Opposition." (Latimer 303) The Americans were also confident of their own safety. "Although British forces had threatened Washington through much of 1813, the American government took no effective action to fortify or defend the capital in the spring of 1814." (303) The Americans believed that the British would not spend the resources to attack Washington because Baltimore was much more valuable militarily. Latimer mentions several cases where the British were angered at the American's approach to war. They were angry about attempted poisonings (305), torpedoes/submarines (306), and snipers shooting from houses (316). This frustration no doubt contributed to the British pleasure during the destruction of Washington. While Latimer notes that not every British soldier was happy at the destruction of Washington, there were many who were. This is especially evident in Latimer's discussion of how the British invaded the White House, joyously feasted on the American celebratory dinner, tried fine wines, and even took time to change clothes before burning the White House (318-319). Latimer also makes mention of the horror and fear that the Americans felt at the advance of the British and the burning of Washington. The Americans crippling panic is best described by Latimer when he recounts the American defeat at Bladensburg. Just after the British crossed the river, American militia men began retreating and fleeing in utter abandonment. (314-315) On page 318, Latimer recounts the horror that many Americans felt at the burning of Washington. One American, Mordecai Boots writes, "so repugnant to my feelings, so dishonorable, so degrading to the American character and at the same time so awful it almost palsied my faculties." (318)

The mood of both the British and the Americans during this whole conflict over Washington are well exhibited in the primary sources that I have selected. In Dolly Madison's letter, we first see the American overconfidence and sense of security in the first paragraph where President Madison asks Dolly if she has the courage to stay in the White House until he returns. Dolly's response is that, "I had no fear but for him, and the success of our army." I interpret this to mean that she was afraid for James Madison's safety at Bladensburg, but did not really worry about the threat of the British actually making it to Washington. However, this confidence is destroyed by James Madison's letters informing Dolly to be ready to leave Washington because the British were stronger than had been originally thought. Dolly is then frightened and documents how on Wednesday she had been looking with her spy-glass for her husband and his friends "with unwearied anxiety" since daybreak. When her husband does not arrive and the British approach nearer to Washington, Dolly frantically stores Cabinet papers, the now famous painting of George Washington, and other valuables from the White House. She then flees the White House with a fearful uncertainty.

|

| From www.dipity.com |

Sources:

"The British Burn Washington, DC, 1814," EyeWitness to History, eyewitnesstohistory.com (2003).

"Dolley Madison Flees the White House, 1814" EyeWitness to History, www.eyewitnesstohistory.com (2009).

Latimer, Jon. 1812 War with America. Cambridge: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press,

2007. Print.

Monday, April 1, 2013

Investigation Using a Secondary Source

I have two primary sources from EyeWitness to History.com. One of these primary sources is a letter by Dolly Madison to her sister about the moments just prior to the British taking the White House. I have several questions about this source. First of all, I wonder if this is one letter or multiple letters. EyeWitness to History.com seems to indicate that this is one letter. However, the letter is broken into three time frames. 1. The day after President Madison left to join General Winder, 2. "Wednesday Morning, twelve o'clock," and 3. Wednesday at Three o' clock. This could indicate that this letter is actually multiple letters. However, I can see how Dolly could have written about three different times all within the same letter; especially if she is writing to her sister years after the fact with the purpose of recounting the events leading up to the British capture of the White House. This leads me to my next question.When was this letter written? The letter itself indicates that it was written just before the British attacked and took the White House. Dolly Madison begins the letter with, "My husband left me yesterday morning to join General Winder." The rest of the first part of this letter (the next four paragraphs) is written in the present tense indicating that it was written the day after President Madison left to join General Winder. The second part of the letter occurs on "Wednesday at 12 o'clock." The third part occurs at 3 o'clock on Wednesday. Both of these sections are written in the present tense. My final question is, why did Dolly write this letter to her sister? Was it simply to recount Dolly's last moments in the White House before she had to leave because of the British invasion, or was there another reason?

What I do know about this source is that it was written by Dolly Madison to her sister. I also know that the events described make sense with what we know about what occurred in the moments before the British invaded Washington, and eventually the White House. I know that the first lady was in the White House as the British were approaching and that she took many valuables (including the famous painting of George Washington) with her as she escaped.

My other source from EyeWitness to History.com is The British Burn Washington, DC, 1814. I have two major questions pertaining to this source. My first question is, why did George Gleig write about the destruction of Washington? Was his purpose to have a personal journal about this major event in his own life, or was it to record an official account for British records? My next question is, who is George Gleig? EyeWitness to History.com makes it clear that Gleig was part of the British forces that attacked Washington. What I am questioning is whether Gleig was a soldier or just some kind of recorder that followed the army around.

What I know about this source is that George Gleig is the author. I know that "George Gleig was part of the British force that attacked and burned Washington." (EyeWitness to History.com) I also know that this source describes events that I am familiar with. The British invaded the White House and ate a meal that had been prepared for the return of President Madison. The British army then set fire to any buildings associated with the government.

My secondary source about the War of 1812 and the burning of Washington is, 1812 War with America by Jon Latimer. This source is interesting because it comes from a British perspective. With this book, Latimer makes the attempt to provide a comprehensive history about the war of 1812 from a British perspective. However, I am primarily interested in chapter 14, "Burning the White House" because this chapter discusses the British take over and burning of Washington. This chapter begins by explaining officer Cockburn's plan to take Washington D.C because he knows that it will be sparsely defended. This chapter also mentions general Ross who is the general of George Gleig, the author of one of my primary sources. This chapter explains how Ross is very reluctant to attack Washington at first because he fears that it will be well defended. However, Cockburn finally convinces him into taking the offensive risk. This chapter discusses how the British forces traveled up river and then marched in the terrible heat (where several soldiers died of heat exhaustion) toward Washington. The battle of Bladensburg is also described in fairly significant detail in this chapter.

However, what is of most interest to me is the attack on Washington, which this chapter also discusses in detail. Latimer explains how Ross has no desire to destroy any private property unless the property's owners began causing trouble. Latimer also mentions the episode where Ross begins entering the city and has his horse shot out from under him (his 3rd horse in this trek toward Washington.) This story is mentioned in the journal of George Gleig. My other primary source (the letter by Dolly Madison) is even directly mentioned in this chapter, but unfortunately it does not say when the letter was written. It only says "Dolley later wrote to her sister..." (Latimer 316). Latimer also explains how President Madison arrived at the White House at 4:30 to get Dolley, but he found out that she had left an hour earlier. Latimer also mentions who took the painting of George Washington from the White House. "It was taken by Jacob Barker, a ship-owner and fellow Quaker, and Robert G.L. de Peyster, "assisted by two colored boys..." (316) Latimer also spends considerable time explaining the British method of burning anything associated with the United States government. He explains how difficult it was for the British to set the Capital Building on fire, how the British set fire to The Library of Congress, and how the British ate the American victory feast at the White House before setting it ablaze. However, Latimer was quick to note that General Ross and Officer Cockburn were polite and considerate towards the civilians who were in Washington at the time of the conquest. After the burning of Washington, Ross and Cockburn quietly left Washington less than 24 hours after they had taken the city. All in all, this secondary source by Latimer thoroughly explains the time frame and events that my primary sources stem from.

Sources:

"The British Burn Washington, DC, 1814," EyeWitness to History, eyewitnesstohistory.com (2003).

"Dolley Madison Flees the White House, 1814" EyeWitness to History, www.eyewitnesstohistory.com (2009).

Latimer, Jon. 1812 War with America. Cambridge: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press,

2007. Print.

What I do know about this source is that it was written by Dolly Madison to her sister. I also know that the events described make sense with what we know about what occurred in the moments before the British invaded Washington, and eventually the White House. I know that the first lady was in the White House as the British were approaching and that she took many valuables (including the famous painting of George Washington) with her as she escaped.

My other source from EyeWitness to History.com is The British Burn Washington, DC, 1814. I have two major questions pertaining to this source. My first question is, why did George Gleig write about the destruction of Washington? Was his purpose to have a personal journal about this major event in his own life, or was it to record an official account for British records? My next question is, who is George Gleig? EyeWitness to History.com makes it clear that Gleig was part of the British forces that attacked Washington. What I am questioning is whether Gleig was a soldier or just some kind of recorder that followed the army around.

What I know about this source is that George Gleig is the author. I know that "George Gleig was part of the British force that attacked and burned Washington." (EyeWitness to History.com) I also know that this source describes events that I am familiar with. The British invaded the White House and ate a meal that had been prepared for the return of President Madison. The British army then set fire to any buildings associated with the government.

|

| From EyeWitness to History.com |

|

| From EyeWitness to History.com |

Sources:

"The British Burn Washington, DC, 1814," EyeWitness to History, eyewitnesstohistory.com (2003).

"Dolley Madison Flees the White House, 1814" EyeWitness to History, www.eyewitnesstohistory.com (2009).

Latimer, Jon. 1812 War with America. Cambridge: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press,

2007. Print.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)